By Satish Mahaldar

Srinagar, Geneva, and the Specter of Abhinavagupta: How an Idea Born of Fire, Ice, and Philosophical Ferment Is Now Weaponized in the Theater of Global Diplomacy

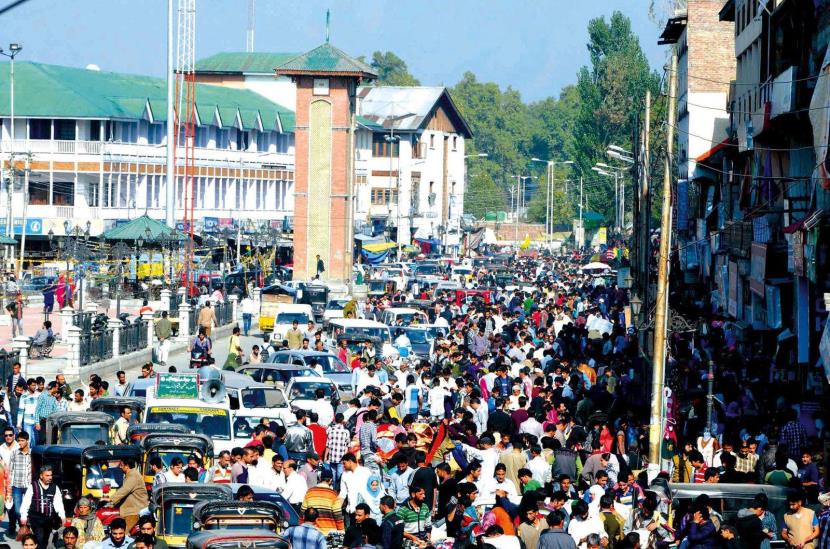

In a world reeling from the ideological fault lines of postcolonial disillusionment, nowhere does the past haunt the present more profoundly than in the contested valley of Kashmir. As nuclear states clash in the high-altitude corridors of Ladakh and a new Cold War simmers in South Asia, one elusive concept continues to emerge from the smoke of geopolitical incantations like a mystical mantra: Kashmiriyat.

But what exactly is Kashmiriyat? A hymn of peace? A mirage? Or a politically convenient relic constructed to mask deeper civilizational trauma?

An Idea Born Not in Battle, But in Debate

In the high halls of ancient Kashmir — not far from the icy springs of Anantnag or the cave of Amarnath, where gods were once believed to speak in silence — a culture was born not in war, but in samvāda, dialogue.

The very marrow of Kashmiriyat, ironically, is older than the word itself. Before the arrival of Islam or even the tremors of Buddhist missionary zeal, Kashmir was a crucible of Sanskritic metaphysics, Tantric mysticism, and Buddhist dialectics. Dialogue, not dogma, ruled these mountains. In the famed Sharada Peeth — once the Harvard of the Hindu-Buddhist world — monks debated the nature of self, consciousness, and salvation.

This Kashmiri pandit intellectual crucible welcomed Islam not with the sword, but with Sufi compassion, embodied in the verses of Nund Rishi, and met colonialism not just with rebellion, but with reinterpretation.

"Kashmir was never a melting pot; it was a crucible — burning impurities and revealing essence."

The Forgotten Architects: Lal Ded and Nund Rishi

It is both poetic and ironic that the foundational figures of Kashmiriyat — Lal Ded, the naked Shaiva mystic, and Nund Rishi, the Sufi ascetic-poet — never spoke of 'Kashmiriyat'. Yet their verses today form the skeleton of the idea.

Lal Ded's defiant assertion — "Shiva resides in all. Do not distinguish between Hindu and Muslim" — is now quoted by diplomats and dissidents alike, from the UN Human Rights Council to street murals in Downtown Srinagar.

Nund Rishi’s Shruks are less verse than vision. In one he asks:

“We came to the world like rain on a flower; why burn the garden to prove it was yours?”

But both saints were less interested in secular pluralism than in mystical realization — something conveniently ignored in modern political appropriations.

Postcolonial Mirage: The Birth of Kashmiriyat in the Age of Nation-States

Like Nehru’s “tryst with destiny,” Kashmiriyat was born at midnight — that is, in the geopolitical vacuum of 1947. With Partition cleaving the Indian subcontinent into competing religious nationalisms, Kashmir — majority Muslim, ruled by a Hindu monarch — became an ideological orphan.

Enter Sheikh Abdullah, who revived the valley's ancient syncretism into a new, secular idiom. In his hands, Kashmiriyat became not just a cultural memory, but a political shield — against both Pakistani irredentism and Indian majoritarianism.

The Indian state embraced this construct, projecting it as proof of the nation’s composite culture. Pakistan denounced it as betrayal. Militants, both religious and nationalist, found it too soft. Intellectuals called it romanticized nostalgia masquerading as ideology.

The Specter of Ancient Thinkers: Abhinavagupta and the Aesthetic Republic

In the shadow of this modern myth looms Abhinavagupta, the 10th-century Shaiva polymath. For him, life was theater — not in the trivial sense, but in the highest metaphysical ideal.

His theory of Rasa, the aesthetic emotion that leads to liberation, makes him a kind of Kashmiri Plato. He saw no contradiction between metaphysics and poetry, between logic and ecstasy. If Kashmiriyat has a soul, it may well reside in his vision of a unified consciousness — where the self, the other, and the divine collapse into oneness.

“No war can be won with reason alone,” Abhinavagupta might have said today. “But no peace can last without it.”

Weaponizing the Spirit: Kashmiriyat in the 21st Century Global Order

As the Himalayan glaciers melt and Chinese highways snake through Aksai Chin, Kashmiriyat has become more than a local ethos. It is now invoked at the United Nations, in South Asian think tanks, and in diaspora conferences in London, Toronto, and Istanbul.

For India, it is proof of democratic pluralism in the face of accusations . For Pakistan, its invocation is a betrayal of the valley's Muslim identity. For the people of Kashmir, caught between curfews and crackdowns, Militants diktak , Cross border terrorism , it is often a memory of a paradise lost, not a reality lived.

Conclusion: Is Kashmiriyat a Bridge, or Just Smoke on the Water?

Kashmiriyat is a palimpsest. It overlays ancient mysticism with modern nationalism, poetry with propaganda. It is at once real and invented, timeless and timely, deeply rooted and desperately needed.

But to reclaim it, we must strip it of its modern masks and return to its origins — to the debates of Sharada Peeth, the verses of Lal Ded, the dreams of Nund Rishi, and the uncompromising metaphysics of Abhinavagupta.

Because in the end, Kashmiriyat may not be an answer. But it remains the most eloquent question the subcontinent has ever asked itself.

In the valley of gods, poets, and prophets, where bullets & cross terrorism now speak louder than verses, the ghost of Kashmiriyat walks still — not dead, not alive, but waiting.

Comments are closed.